Honoring a legend: the story of the most decorated enlisted sailor in Navy history

BY Jack Dorsey The Virginian-Pilot

Jul 17, 1997

James Elliott Williams wasn’t looking for medals when he went to Vietnam, even though he ended up with nearly all of them, including the Medal of Honor.

He just wanted to show he had “something else between the ears” other than his ability to chip paint and salute. He got that opportunity more.

Williams is credited with damaging or destroying 65 enemy sampans and junks during a three-hour fight on the Mekong River, where he led his two small patrol craft in a fierce battle.

This morning, the 67-year-old Florida man is being honored again.

Special Boat Unit 20, based at the Little Creek Naval Amphibious Base, will name its new headquarters the BM1 James E. Williams Building.

“I’m excited and pleased,” Williams said earlier this week from his Palm Coast, Fla., home near Daytona. “There are very few times in a man’s life he gets these kinds of honors.”

Williams has become a legend to the sailors who fought aboard the small special warfare craft during the Vietnam war.

At 36, with his retirement papers nearly in hand – he enlisted when he was 16 – Williams asked to go to Vietnam to finish his career in command of a river patrol boat. His was No. 105. He actually became boat captain and patrol officer, in charge of two boats.

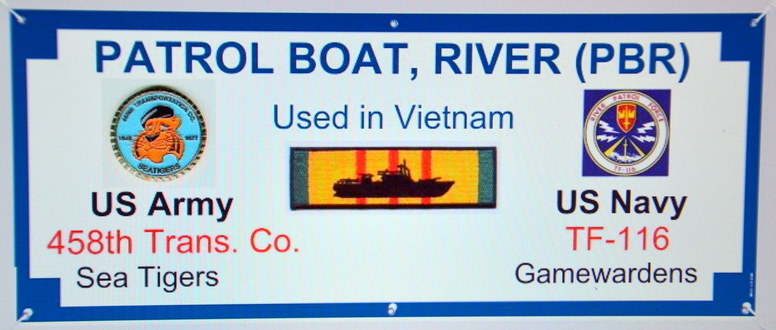

The 32-foot fiberglass and armor-protected boats carried a crew of four and plied the inland waters of Vietnam, searching for supply-carrying junks and sampans that aided North Vietnam.

Williams had served in Korea and spent most of his time aboard large Navy ships. But it was the river patrol boat he wanted most.

For a ninth-grade dropout who thought of the Navy “as my second mom and daddy,” this was an opportunity to show that a senior enlisted man had something more to give, he said.

“I looked at it as an opportunity to do something better. So did all the others. That is why the PBR was so successful in Vietnam. The men were so proud.”

Williams recalls the afternoon of Oct. 31, 1966, in vivid detail: “When you want to forget, you can’t,”‘ he said. It was a day patrol, sort of a “relax-and-recreation” patrol as opposed to the more dangerous night operations the crew had just completed.

“We were just dee-dee-boppin” down the river when the forward gunner . . . hollered there were two high-speed boats crossing ahead of us,” he said.

“We all got real alert. These boats had twin long-shaft motors, Mercury outboards, and they were tremendously fast, over 40 mph. That usually signified some high-ranking officers aboard.

“Then they started firing at us. We returned fire. One went to the north bank and the other to the east. We gave chase to one and . . . eliminated him.”

Williams’ crew then turned to pursue the other boat and watched as he cut into an eight-foot-wide canal in front of a rice paddy.

“Looking at the map, I could see where he had to come out. I turned hard right to wait for him. As I did that, lo and behold, we found a big staging area. All I could see were boats and people.”

Putting out a large wake as he sped across the water, Williams plowed through the middle of the formation.

“They were shooting at us from the right and left and we were shooting. They were doing more of hitting each other than we were.

“We got through that and I am trying to zigzag. . . . I go by a couple more corners and turn into this area . . . and lo and behold, we hit the second staging area.”

Again, they sped down the center, guns blazing and radio squawking for help from friendly helicopters.

As his commander appeared overhead in a helicopter, he told Williams he was about to make a strafing run and asked Williams his intentions.

“I said, ‘Damn if you are going to leave me in here.’ So I followed him back out and that is when we hit the big (ammunition) junks and blew them up,” Williams said.

It was a rout of the enemy. When it started getting dark, Williams could tell the enemy was ready to give up. He ordered his boats’ search lights turned on, despite the added attention it drew to him.

“I know people have questioned my judgment many times since then and probably always will, asking why did I turn on the search light,” he said.

“It was obvious they were whipped, giving up, throwing their arms down. We didn’t lose a man. That’s saying something. We had some wounds, but nothing serious.”

Williams received shrapnel wounds in his shoulder, chest, side and head.

When he returned home a year later, Purple Heart in one hand, the Navy Cross, two Silver Stars and three Bronze Stars in the other, Williams was asked to remain in the Navy. He was promised a promotion to chief.

But he had accepted a job with the U.S. Marshal’s office in South Carolina. He retired from that second career in 1983 after taking over all field activities in the nation.

Besides, he wanted to go home to his wife and family. He has been married nearly 48 years, has five children and eight grandchildren.

The Navy made Williams an honorary chief in the 1970s, he said. Made him go through the traditional initiation and all.

As for the Medal of Honor – the nation’s highest military award for bravery – Williams said he was stunned when he learned it was to be presented to him two years after he retired from the Navy.

“I was just doing a job to the best of my ability. I wasn’t out there trying to win medals. Events just happened.

The 105 and the crew, we were always into something or other. We weren’t looking for it.”

CAPTIONS:

Photo – HUY NGUYEN/The Virginian-Pilot James Elliott Williams

Graphic THE NAVY THIS WEEK [For complete graphic, please see microfilm]

END OF CAPTIONS